Emily Carroll’s web-comic, His Face All Red, focuses on two main characters—the Narrator and his Brother. Neither is named in the story, therefore I have capitalized their titles for referencing purposes.

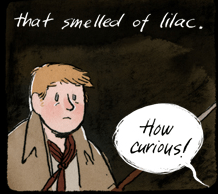

The Narrator immediately builds sympathy for the Brother by describing him as handsome and trustworthy, while painting himself as envious and unpopular. Due to an unreliable narrator, the only thing I can tell for certain what is true are his emotions, as his story may have untruthful elements pertaining to events and appearances. For example, it is not clear if when the characters pass by a tree and stream whether the descriptions are simple similaic descriptors, or if the trees and streams in this fictional world actually look and sound like that.

After the Narrator kills the Brother, he is celebrated for slaying the beast that was terrorizing the village and is given his Brother’s animals. He seems content here, as he notes he dreamt of nothing. One part of the story is that the Narrator is the only one who notices the Brother’s coat is not missing the piece he ripped from it. If the Narrator really did take a piece and show it to the townspeople for proof of his Brother’s death, why then was he the only one who noticed? I suppose everyone could have been too overcome with joy to notice for themselves. This is peculiar nonetheless.

The Narrator seeing the Brother at night digging could be a hallucination or an actual event, but at this point in the story he is just as confused as the reader, if not more so due to him not being entirely normal/sane at the beginning.

In the hole the Brother was deposited into, the Narrator comes across a body. Personally, it was hard for me to tell if it was the Brother’s or not as all that was shown was some hair and an eye (and the outline of his jacket I suppose). It is possible that it could be the Brother: the Narrator had just finished asking why the Brother who had come back does not look at him, implying his Brother usually does. The eye shown looking at the Narrator in the final scene could be a reference to that. It could possibly be any sort of dead body. What the Narrator finds may not even be real; he could be imagining whoever/whatever he found down in that hole, as his mind is clearly not in the best shape.